A response to the politicising and commercialisation of queer African creatives

A collaborative project by Somunachino

Words by : Adebayo Quadry-Adekanbi

It would seem queer African existences are a never-ending performance of resistance. We resist the normativity that sees to shame us for being queer. We resist the erasure in queer discourse that forgets we exist and neglects that we have been queer before they gave queer its language. We resist our representations as monolithic Africans, where Black is King, and Black Africans in the diaspora can find their way back for a year of return to a supposed safe haven where queer Africans on the continent are far from safe, punished and closer to death for being queer.

Our existence needs to be in resistance to… in opposition to… in refusal to… something. Our creative decisions need to somehow articulate something we are trying to say about our gender; the sex we have (or not have), and who we choose to have it (or not have it) with; the death that awaits us in and out of our community; the erasure we experience from global discourse; or how hard our lives must be for being not only queer but Black and African. Our identities exist to be tools of commercial politics.

When, during this resistance, do we get to experience joy, without it being a political act of resistance that is commodified, packaged and reduced to queer, Black or African? Where do we go when we just want to create and be seen for the works we have created and not the statement we may or may not be making? When do we get to opt-out of the agenda?

The personal is political, but is there a time when the personal doesn’t have to be political? Can we be queer, Black and African without politicising our work or people reading politics into our work? Art and creativity aren’t just political tools; they can be acts of self-expression and sights of joy and safety. Lunalovesyou, a singer, sound engineer and model, says, “queer people have faced a lot of backlash, generally speaking, and I feel as though my music is a safe space for me. I don’t want people to turn it into a political playground where they have the chance to debate whether my existence is worthy or not. I do not think my work is political in any way. And I like it that way.” Israel, a stylist, highlights, “I like to think of my creativity as something fun, and I feel like activism is nothing to play with. This is real life. I don’t like mixing activism and creativity. It can work, but if it’s not done right, it can be very insensitive.”

To disrupt normativity, we stray so far away from the mediocre, from the simple, and the resistance in simply existing without the need to negate every aspect of a world that wants us punished. PBK, a fashion designer at PBK Apparel, says she creates because she likes clothes. That’s simply it. For PBK, “queerness is not embedded in my designs. It [her brand] is just about me as a person” The decision to make her clothes unisex is not a mission to disrupt normativity; it’s a sight of joy, It’s not about anyone else or being queer, It’s about being PBK.

Notably, because PBK does not intend to be political, does not make her actions or designs any less so, but this is a politicising that starts from PBK and centres PBK, not in opposition to society, but as an individual – a creative – who is being creative and finding joy in that. It is not about producing a commentary on society. PBK is not centring the education, politicising and performance of society. PBK is simply existing, and society is along for the ride. As PBK puts it, “I’m not really designing for other people. If people buy my stuff, they buy my stuff… it’s really just what I like, and that’s what I put out there.” Essentially, it’s not about us; it’s about PBK.

As queer African people, our bodies are archives. We carry the archival memory of our existences that resists many parts of our contemporary society in the context of our history. We might not be meaning to be political, but that does not mean we are not political. Merely being alive is political. Amam, a make-up artist highlight this, “existing as a queer person, I’m non-binary, I’m Black, I’m pansexual. I feel like my existence is already politicised. My existence is already an act of activism.”

Our existence might be political; however, so is our joy. Amam mentions that they have people “placing expectations on me or trying to commercialise my work; saying, ‘oh! You should start a YouTube channel’ or ‘start a make-up Instagram’… maybe I just want to do make up for myself.” In a world that sees to either punish us or make us a spectacle for their entertainment, we should be allowed to be neither punished nor seen by our punishers. Some of us find joy here, and some of us deserve to find joy here. Sometimes, our joy comes from knowing that our existence serves no other purpose than to serve us and allow us to experience peace and joy. We should be allowed to centre ourselves and our joy.

That we can be creative, expressive and beautiful without the added effort of making a political statement or educating or resisting. This, in itself, is an act of resistance. This is political. But it’s a politics of joy. We are not beginning from a place of scarcity, lack of ‘not enough,’ like we are often expected to. We believe that we are enough, and our creativity does not have to stand in opposition to something or someone to be valid. We are centring ourselves and our joy.

This does not mean what is created does not have implications. Art can and should be critiqued, and much of the critical analysis of art is political. It is essential to recognise that queer African creatives do not exist in a vacuum. Our art can inform political discourse. Also, it can be difficult, as a creative, to show up and be seen because of how people will accept your work. How do you let yourself be seen in a world that sees things in black and white, good and evil, beautiful and ugly?

This is where reflection and power come into play. While we create for self-expression, it is essential to reflect on how our creative projects can inform our political climate. This is particularly important considering how class and social capital can affect the material realities of who gets to and can afford to create ‘just because,’ and who has to buy into the politicising and commercialisation of queer arts as a means of survival. We need to question our positionality when our art is being critiqued and hold ourselves accountable for our presence in and out of our communities. As Amam mentions, “being able to do these things is not something that people in the community I’m a part of have the freedom to do… I’m in East London doing make up for people in a queer space, and I know for a fact that I cannot do this in Nigeria. I know there’s also privilege and the class that allows me to create a sort of ‘safe space’. But even with that privilege and class, I’m still not shielded or fully protected from the harm that exists there.”

A part of operating from a place of joy and enough, instead of scarcity and lack, is recognising that our self-worth is not on the table when we are critiqued because we are good enough. Lunalovesyou mentions, “if you want to be truly happy, you have to block out a lot of what everyone is saying… as long as you have a strong conviction in what you are doing.” This allows us to take on what is constructive and useful, disregard what comes from a place of shame and lack, and understand who is critiquing, what paradigm they exist, and why our art might evoke certain reactions.

This is a response to the commercialisation of queer African creatives because this project came together not for the commercialisation of queer African creatives, but as an expression of creativity by queer African creatives that has no interest in being commercial, political, queer or African. It just is.

The irony here, however, is that this piece, in itself, can easily be read as a form of political discourse. But instead of seeing it as political discourse, see it simply as validation and justification for our project to get together and create just for fun and for joy. We are not making a statement about our identities. If anything, we ask to be freed of its burden for once. We simply want to create.

It’s above us now. When this is received, critiqued, read and politicised is when it becomes political. How it can and perhaps will be disseminated and co-opted is how the political becomes commercial. But for us, this was simply joyful.

Credits

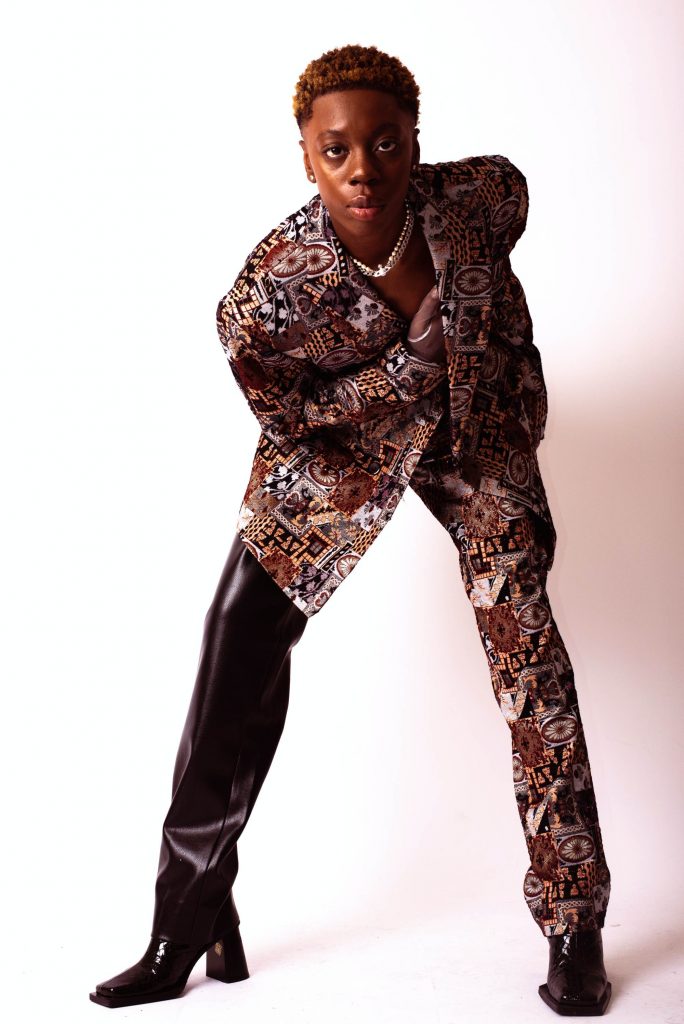

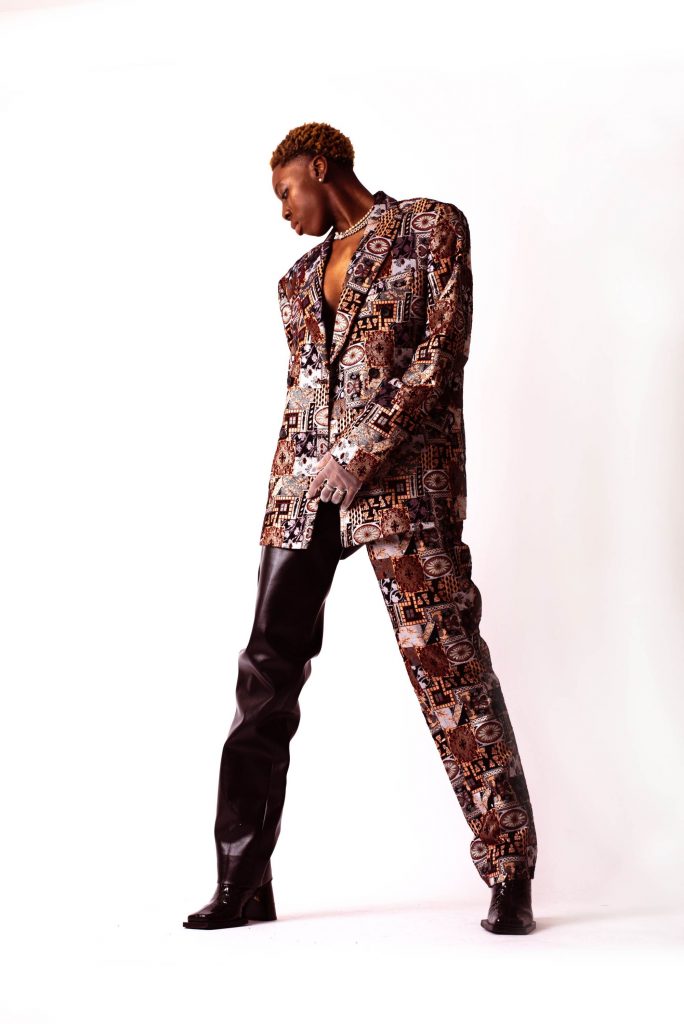

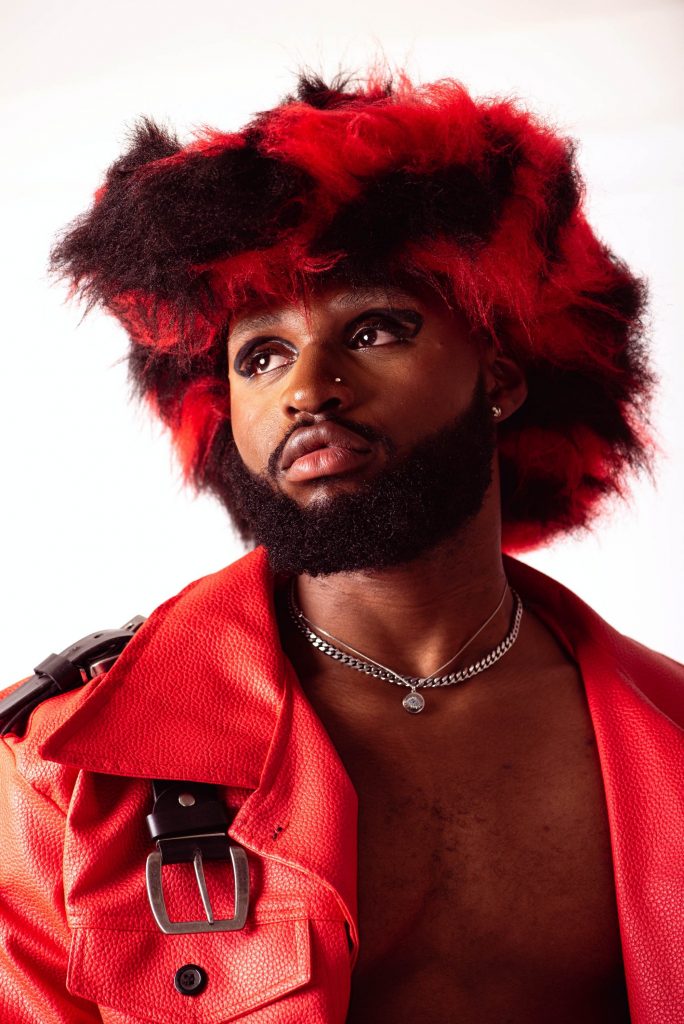

Creative Director: Muna @somunachino

Stylist:

Israel Runsewe @isrrrrl

Makeup Artists: Amam @okayamam_ Chelsea @cheuoooo

Models:

Luna @lunalovesulani PBK @pbk.s Innocent @enyereibe

Writer:

Adebayo @adebayoqa

Pieces by: @vangeiofficial @tokyojames @frucheofficial

Creative Direction Assistant: Anisha @neesheeneeshee

Special thanks to: @kevweumusu @msoge