Every Nigerian has a good memory of movies that incite a broad stream of emotions from the good old days. These movies showcased the rich Nigerian culture and served as a tool for teaching morals and traditions of the different tribes of the black Nation while passing down some fractions of what the Yoruba people call “Lori Iro” through exaggerated visual effects. Filmmaking in Nigeria dates back to the ’80s and has experienced different levels of growth with each generation of producers, actors, directors, and cinematographers, among others.

Filmmaking in Nigeria is not limited to movies and shows but extends to soap operas, musicals, and fashion films and has experienced growth over the past decade, with the emergence and expansion of millennials and Gen Z creators alike contributing to the development of several creative niches. More fashion films, short films, movies, and shows have successfully stood out as the creative industry churns out animators, scriptwriters, set designers, producers, and more in the evolving film industry.

In every thriving industry, there are several interests as to the process behind the making of the products and how they successfully penetrate foreign markets. In the Nigerian filmmaking space, there are many misconceptions about what happens behind the scenes, and the expectations of the audience nationwide continue to grow.

The Nigerian Film Industry (Nollywood) is recognized globally as the world’s second-largest film industry. Nollywood plays a significant part in the Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation Sector contributed 2.3% (NGN239 billion) to Nigeria’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2016 and an estimated $1billion in export revenue in 2020, according to a report by PwC’s Global Entertainment & Media Outlook 2017 – 2021.

Several developments have contributed to the transition from Old Nollywood to New Nollywood, including technology, larger budgets, extended film production periods, and better-equipped personnel for storytelling. The advent of video-on-demand platforms and pay-TV networks is another way technology has helped the industry. Cinemas have fostered a connection between films and their audiences, but some viewers do not see these films because they lack interest.

In 2020, Netflix launched locally in Nigeria and South Africa to prioritize content made by Africans. Since then, it has commissioned a few original TV shows and films, most recently Kemi Adetiba’s seven-part series King of Boys: The Return of the King. Before its launch, the streaming giant had also been paying for content by Africans for streaming on its platform.

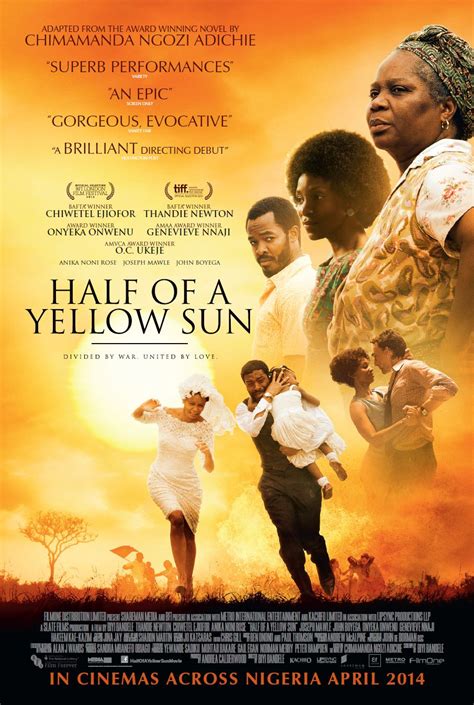

With more streaming platforms archiving old classics and social media’s influence in spreading memes from big players such as Aki (Chinedu Ikezie) and PawPaw (Osita Iheme), Chiwetalu Agu, Sam Loco Efe, Nollywood has received global fame and sparked curious interest from the foreign audience. As new content is presented, Nollywood films have an increasing demand from audiences far and wide. Another way Nollywood has utilized globalization is by casting foreigners in their productions to capture diverse demography, as seen in Biyi Bandele’s Half of a Yellow Sun which cast Thandie Newton, Anika Noni Rose, and Chiwetel Ejiofor in lead roles, and ‘Namaste Wahala’ with Ini Dima Okojie and Ruslaan Mumtaz.

Considering how much growth Nollywood has seen, it would be easy to think that the industry is at its peak. However, there are existing challenges to be dealt with for Nollywood to go forward and achieve new exploits.

In this article, I chat with two distinct Nigerian filmmakers in an attempt to unravel various notions and constraints surrounding filmmaking in Nigeria, Collaborations, and how to succeed in the task ahead.

Barnabas ‘Barny’ Emordi

The Lagos-based Cinematographer, Director of Photography, and Filmmaker is popularly known for his exceptional work on The Ghost and The Tout Too, Dinner at My Place, ‘DOD‘ (The first Nollywood time travel film), Multi-award-winning Elevator Baby film, Prophetess, several TV Commercials, Documentaries (Local and internationally), and a host of other blockbuster movies. his outstanding filmography culminated in him being named the highest-grossing Director of Photography in Nollywood for 2021.

Barny, who recently got nominated for Best in cinematography at the AMVCA for his work on the movie Superstar, gives an in-depth look at collaboration and the growth in the Nigerian filmmaking industry.

What’s your take on collaborations in the Nigerian filmmaking space?

Barny: For me, collaboration has always been a fascinating idea. There is no question that top-performing films and the rapid growth of the film industry have all resulted from a collaborative effort between filmmakers, so collaboration is something you should not discount.

Over the past few years, several big studios have collaborated to make small, medium, and large-scale films, and younger creatives have imbibed that spirit to work on projects together from short films, feature films, and documentaries to produce good projects. I have worked with several individuals as well, and it has always been an incredible experience, so I feel it’s pivotal for our growth as an industry.

What is the most challenging aspect of making a blockbuster?

Barny: So, there’s a common phrase that money is not always an issue, but frankly speaking, if we’re talking about blockbuster films, money will always be central to the outcome of whatever film you’re making. Presently in Nigeria, blockbusters are considered films that have grossed over 100 million Naira at the cinema. We need to understand that such films need resources so that you don’t have a big idea and no ability to execute.

With filmmaking in Nigeria, we are at a level where we have capable hands to pull off blockbusters. However, putting personnel together, equipment, post-production, and all that requires a lot of resources that are not always available. So, it’ll be okay to cite finance as the main barrier to not blockbusters but top-quality cinema films. Off the top of my head, small-scale quality films can range from 15 to 25 million, medium-scale films can range from 30 to 65 million, and large-scale films can be upwards of 80 million, depending on the story and marketing plans involved.

The film industry is a bit dicey now because we are not making enough revenue to sustain the culture and height we want to grow to be. There aren’t even enough screens in the country to aid in grossing over 100 million or 200 million Naira in the opening weekend. So with that in mind, there aren’t a lot of investors willing to front such an amount for a film because it may not break even in the first six months of release. Producers producing films at such levels are doing a lot, and it’s not as easy as people think for filmmakers.

Apart from budgeting, what other constraints limit the execution of top-quality cinema and box office movies?

Barny: The Nigerian film industry has been growing at a terrific pace, and it’s evident to everyone that we’ve had commendable growth over the past decade with a lot of room for improvement with our skillsets for production crews. At the moment, there is still a lot of re-education needed for production crews so that we can align with global best practices and compete globally. It is an ongoing process, and thankfully, there have been a lot of initiatives, academies, and film institutes for actors and crews. However, we also lack some infrastructure and tools that can give us an edge on the global scene. Our equipment rental services are doing their best by bringing in new tools and making them available for filmmakers, so it’s an ongoing process. As we grow and advance technically, we will continue to evolve as things fall into place.

What kinds of films do you think Nigerian filmmakers could make to allow for better recognition?

Barny: Storytelling and filmmaking are universal interests that people of all cultures and tribes share. In the aspect of storytelling, Nigerian filmmakers are doing a lot. We are currently making films from multiple genres, including drama, romantic comedies, and even superhero movies in line with our Nigerian culture (such as King of Thieves). Filmmakers are constantly making an effort to make films that touch on a wide range of genres.

In terms of post-production, we are not there yet with Marvel-level films, and that’s because such films require more resources and infrastructure that we do not currently have access to and thus create a barrier to the execution of such ideas. There are a lot of talented scriptwriters and filmmakers with intriguing stories, but without the right resources and structure, it’ll be difficult to tell these stories. We’re working with what we have, and filmmakers are currently doing their best.

Concerning collaboration, what challenges have you experienced and consider barriers to working with other creatives on a project?

Barny: In my experience, the most credible challenge is getting people together that align with the core vision of the project. Apart from resources that can hinder onboarding collaborators on a project, the most important aspect of collaboration is having like minds who can bounce ideas off each other without drifting apart from the core vision. In some instances, collaborators may come on board, and ideas begin to clash and ruin the goal of producing a great film.

Additionally, collaborations must go through the proper channels and ensure legal aspects are covered so that no loose ends arise at any point of the production.

What growth paths do you recommend for Nigerian filmmakers and the industry to follow to achieve the desired heights?

Barny: Firstly, as much as we’re growing, we need to be better structured and have more infrastructure. Most top players in the industry are playing on their turf right now because there isn’t any alignment within the core. In terms of financing, we’ve had a couple of filmmakers benefit from foreign investors, but it’s less than a handful, so if we have more influx of investors, it would also help move things at a faster pace.

There is a need for more film villages, cinema screens, studios, VFX, and more infrastructure. A lot more heavy lifting is required to attain that next-level status. Filmmakers and producers are doing their best with the current environment and resources available. With a better atmosphere and more resources to create and distribute, we will have better films, and filmmakers can also generate more revenue to keep the cycle moving.

Godwin Josiah Gaza

Godwin is a visual creator with The Critics Company based in Kaduna, Nigeria. Godwin’s creative portfolio spans filmmaking, scriptwriting, and direction, with over eight years of experience in the filmmaking space. He creates dialogue, the characters & the storyline of the scripts. His unique scriptwriting skill has earned him a permanent place in the league of writers, among notable directors like C.J ‘Fiery’ Obasi and Kemi Adetiba. Noteworthy projects include Z: The Beginning, King Of Boys 2, and the recently released The Click, to name a few.

Speaking on collaborations in the Nigerian filmmaking space, he says: “working with other creators on film projects is always an interesting experience although it comes with its challenges. It creates room to explore beyond what you are used to working with. Working with Kemi Adetiba on The King of Boys 2 as a VFX artist and supervisor, was a different experience for me and my team. Asides from being a mentor to me, she allowed us to experience what it means to be on the set of Nigeria’s first Netflix Original series. It was very demanding in terms of expectations and likely critique, but insightful and gave collaboration a new meaning. Nigerian creators are very talented individuals who give their all when they want to.”

When asked what he considers one of his biggest challenges as a filmmaker, Godwin sheds light on working on ‘The Click’. “So my experience with ‘The Click’ was different from my other projects because we had to work with a tight budget, and in the creative space, funding can be a significant constraint to bringing your ideas to life. As Buju (BNXN) said, if you no get money, e dey kill idea. Nonetheless, we had to work with what we had to make a good film.”

Godwin makes it clear that with the enormous amount of talent in the Nigerian filmmaking industry, finance is a major hindrance to the execution of innovative ideas. He explains that the major reason a lot of producers and directors are limited to releasing sub-par movies is they have to work with little financial backing compared to the millions of dollars invested into filmmaking in Hollywood.

He also emphasizes gatekeeping in the Nigerian filmmaking space. More compelling stories could be told but may not have the funds to bring them to light. Ideas already produced are often dumped on YouTube because the capable production and distribution companies may not make those opportunities available to the creators. While touching on possible solutions to foster growth in the Nigerian film industry, he suggests international production companies extend film budgets to Nigerian filmmakers with compelling stories. Additionally, production companies and distributors with sufficient funding should provide opportunities to all types of creators, regardless of age or popularity, if ideas for better films are available.

After speaking with Barny and Godwin, two filmmakers from relatively different backgrounds and skillsets, it is clear that finance is a significant limitation to growth in the Nigerian film industry. In story-telling and filmmaking, collaboration stands out as a positive force to foster growth and development for entrants to filmmaking in Nigeria.

As filmmaking in Nigeria evolves, there is optimism in the expectations for the rapidly growing industry in a few years. With increased foreign investments, the next decade should invoke immense growth for filmmaking in Nigeria.